Badly damaged by the tsunami of March 2011, the region is being rebuilt, partly thanks to this drink of the gods.

Badly damaged by the tsunami of March 2011, the region is being rebuilt, partly thanks to this drink of the gods.

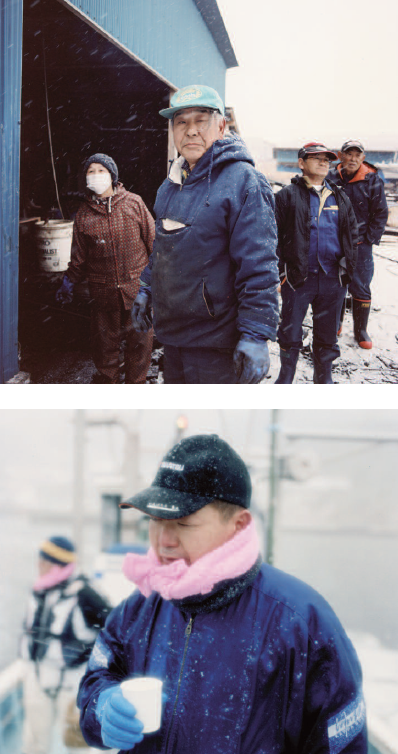

If I were asked to characterize the spirit of Tohoku I would tell you to look at the local sake breweries. I would probably also add that sake has been part of the Japanese DNA for the past two millennia. In the old days people thought that sake was a sacred drink brewed by the gods. They thought that divine power penetrated their bodies thanks to sake. Since the events of March 2011, the Tohoku region has become a high quality sake production centre. The listing of Japanese cuisine as an Intangible World Heritage by UNESCO, the promotion of Cool Japan worldwide and the national Kokushu project launched in 2012 to promote sake, should all help boost Tohoku’s sake, both in Japan and across the world. Three years after the disaster, while travelling along the coast in this region, I realized that many of the wounds caused by the tsunami hadn’t yet healed. The local industry still hasn’t been rebuilt and in some places the workers are still clearing the debris left by the tsunami. Most people live in little prefabs far away from their native city. The young people have left; only the elderly have stayed. In Kesennuma alone, over 1,400 people died, 80% of the local businesses were damaged and 80% of the people working in the fishing industry lost their jobs. Despite this desperate situation, nearly all the breweries in town that were hit by the tsunami picked up the rhythm of their high quality brewing and carried on making local sake (jizake).

Produced from the region’s rice and water, this drink pays tribute to the spirits of all those who have disappeared. “High quality sake breweries in Tohoku could possibly now become the most popular in the sector,” says Sato Jun from the Japanese Economic Research Institute that uses statistics issued by the government. “Because of the popularity of this sake, Tohoku’s future is bright,” he adds. Since the 11th of March, the ‘Let’s drink Tohoku’s sake’ campaign, designed to support the areas hit by the tsunami, has reached its objective. Before the disaster, most of the jizake produced here was drunk locally. Now it is found in Tokyo, in other prefectures, and even abroad. Tohoku brewers travel to the United States and France, as well as other countries, to promote their sake and Tohoku’s jizake encourages breweries in other areas to follow the example of those in the worst hit regions. Japanese consumers have discovered the unique taste of these beverages thanks to the brewers in Tohoku, and they have started drinking more of them. Jizake’s rise in popularity also gives hope to the rest of the profession that has seen the consumption of sake decline since the mid 70s. According to Takeharu Tomohiro, editor-in-chief of Bacchante magazine, at least a hundred new sake bars have recently opened in Tokyo that only serve regional sake.

The owners are often young people and 70% of their customers are also young and many of them women. While in the capital people are enjoying discovering jizake, in the areas that were damaged the drink remains a ritual source of comfort, by which people can connect with nature and the spirit of those who have died. After the 11th of March, the role of local sake was crucial for the people who were evacuated. Jizake has always played a part in every period of life. From birth to death, as well as at weddings, the construction of houses or the launching of a new fishing boat, sake has a its role in every one of these moments. Behind every one of these breweries full of hope is the determination and devotion of sincere men who are akin to abstemious, hard-working monks in monasteries. Kesennuma is a famous fishing city in Miyagi prefecture and home to the Otokoyama brewery, founded in 1912. This brewery restarted its sake production a mere two days after the tsunami hit, even amidst the chaos of the aftershocks. “People asked me to get back to work in order to keep the local industry running,” recalls the brewery’s boss Sugawara Akihiko. “We had no electricity or petrol. There was no light, no water, but we decided to start up production anyway.” he tells. And he was right to do so. Thanks to the distribution of sake and other products, people took interest in Kesennuma and the media arrived en masse to cover the event. “As a local brewer, I needed to raise hopes with Kesennuma’s sake,” adds Sugawara. “There was no way we could compromise our aim of producing the best sake. Even if it meant I had to resign or the company went bankrupt, I would go on making sake”. Rikuzentakata in Iwate Prefecture is only a few kilometers north of Kesennuma and saw 1,773 fatalities from the tsunami. The city’s symbol is a pine tree, the only one to have survived the disaster. The Suisen brewery, a cultural icon of the city, lost everything after the tsunami and several employees were carried away by the great wave. Thanks to the presence of hundreds of cherry trees and local people who would gather to admire the trees in bloom, the gods have always blessed this brewery. It is a place that strengthened the ties between the local population, their ancestors and nature. There was a miracle, even as everything was swept away by the fury of the tsunami, as one barrel of sake escaped the disaster, balanced on the top of a pillar. It was taken to be a profound message by the brewery, as this was the first in a series of 36 decorative barrels and bore the number one 1. “When I saw it among all the mess, I took it to be a message encouraging us to continue making sake and rebuilding the place,” says Konno Yasuaki, a master-brewer at Suisen. He accepted the challenge and restarted the sake production on another site in Ofunato, near Rikuzentakata. Neither the tsunami, nor the Fukushima nuclear power accident succeeded in breaking the cycle of sake brewing. Suzuki Daisuke, who succeeded Suzuki Shozo, transferred his brewery to Yamagata prefecture, where his family was evacuated after the earthquake. The original site was just 6 kilometres from the stricken power plant. On the 11th of March his brewery was swept away, and the rice farmers with whom he worked all died. Both his company and his city were completely destroyed but three days later, his neighbours came to see him to ask him to continue making sake. He agreed and kept his word. By a miracle, some shubo (yeast starter), an essential ingredient in the production of sake, had been sent to a laboratory outside the city. It allowed him to start up production again only two months after the disaster. He had to go into hospital with depression but nevertheless continued to make his sake with the profound hope that it would reunite his neighbours who were now scattered across the country. “I continue brewing sake, hoping it helps and so that the flame of my native city will not be extinguished,” he says.

For the Festival of the Dead in summer 2011, an important time to comfort and welcome the spirits of the deceased, he produced 2,000 little bottles of sake that he sold to refugees in Namie in the space of only two days. “When I see the spirit of sake blow through Tohoku, I think of life as eternal. I see the baton passing from father to son, and so it carries on. Jizake has always been associated with the continuity of life” says Goko Jun, a member of the Association of Sake Brewers. According to this organization, there are very few damaged breweries in this region that stopped making sake after the events of March 2011. Out of 224 breweries active at the time, 11 were completely destroyed by the tsunami and 4 were closed because they were situated in the 20 kilometre wide exclusion zone around the Fukushima dai-ichi power plant. The day after the earthquake, the organization launched an appeal for donations that amounted to 70 million yen to help breweries that were damaged. The popularity of sake is rising fast. According to the tax authorities, exports broke all records in 2012 with 14.1 million litres sold abroad, twice that in 2001. Many consider that it has huge potential with numerous advertising campaigns and the forthcoming 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo. If this is confirmed, the reconstruction of Tohoku could be greatly speeded up thanks to its local sake. One could ask why so many people have taken to regularly drinking jizake, even those who live beyond the boundaries of the disaster areas. “I believe that the cultural DNA of ancient Japan was awoken by the catastrophe. Jizake is made in total harmony with nature, in line with the DNA of Japanese cultural heritage,” says Kanzaki Noritake, a folk craft specialist and priest at a Shinto sanctuary in Okayama Prefecture, in the southeast of the archipelago. “For a long time, people have thought that sake embodies the spiritual power of the gods, and that it was brewed by the spirit of nature at large. When a huge natural disaster takes place, the Japanese unconsciously remember the presence of a kind of higher power and turn to prayer to ask for help. So they start drinking the local sake of their ancestors in a sort of shamanic act, and a return to the roots of their cultural DNA,” he adds. The temperature is now below zero, but the brewers remain busy and put all their heart into producing the best sake. The sakagura (breweries) of the Tohoku region are sanctuaries that nothing will destroy, not even an earthquake, a tsunami, or a nuclear disaster. Simply because they embody the spirit of the Japanese.

Makiko Segawa

Photo: SASAKI Ko