The Edo-Tokyo museum opened in March 1993. In the space of twenty years it has become an essential tourist destination.

The Edo-Tokyo museum opened in March 1993. In the space of twenty years it has become an essential tourist destination.

When you take a walk in Tokyo it is hard to imagine what the capital was like just a century ago. Unlike many other big cities around the world, there are very few places that give an idea of what life was like in the world’s biggest city at a time when Paris and London were competing to be the centre of the world. Natural disasters such as the great Kanto earthquake in September 1923 and the air raids during the Second World War, such as those that took place in March 1945, destroyed practically everything.

Finally, rebuilding of the infrastructure destined to modernize the city and prepare it to host the 1964 Olympic Games succeeded in completely destroying the urban landscape. Many districts that had begun to be rebuilt after the war were completely disfigured by the great construction projects. Some rivers disappeared, trams gave way to the underground and motorways were built above canals and over several historic locations such as the Nihonbashi bridge, from where the country’s main road network started. It was thus hard for the city’s population to forge an identity for itself and reconnect with their historical roots. Even more so since the 50s when the capital started welcoming people from the provinces looking for work in its burgeoning industries. It is not a surprise that nowadays people associate Tokyo’s history with places such as Ueno station, where migrants from the north of the archipelago first entered the city. A few remnants of the past can be found here and there, but they are not as concentrated as in other capitals around the world and people cherish the few places where the past has been preserved. This is very much the case with Shibamata, a district in the northeast of the city.

Film writer Yamada Yoji made it the birthplace of his famous character Tora-san, the hero of the longest cinematographic series in history (48 films): Otoko wa tsurai yo [It’s tough being a man!]. This is why the city’s authorities, and in particular governor Suzuki Shinichi, decided that there was a gap to fill and that creating a museum was a good way to help people reclaim their history, be proud of it and feel like they are a part of its development. It is no surprise that it ended up being called Edo-Tokyo Hakubutsukan (the Edo Tokyo Museum), to highlight its journey through history. It was also not surprising that it was built in Ryogoku, a popular district where the bridge of the same name, which played such an important historical and economic role, spans the Sumida river. Ryogoku is also famous for engravers and as a centre of sumo, being one of the important areas in the development of Japan’s ancient national sport. Created by architect Kikutake Kiyonori, the museum building takes the form of a sweeping roof supported on large pillars and is very distinctive on the local skyline. It opened on the 28th of March 1993 and celebrates its twentieth anniversary this year.

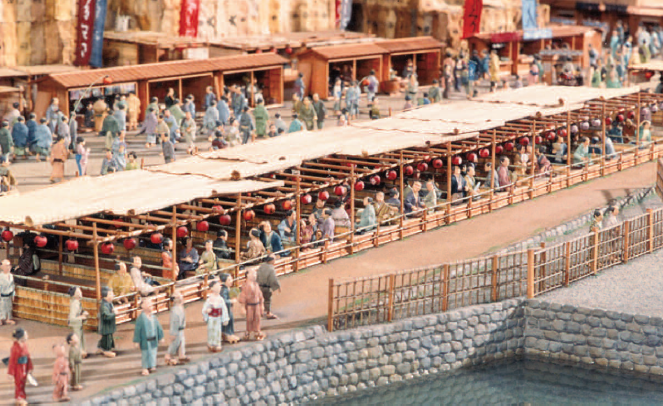

Over the years it has cultivated many dedicated regular patrons and has visitors that regularly return for the permanent or temporary exhibitions that take place two to three times a year. “The main idea of this project was that the Edo-Tokyo Museum was to be a friendly location in which visitors feel at home and learn about their history”, says curator Iizuka Harumi. Many objects are displayed behind glass because of their fragility, but visitors are allowed to touch many more and to take part in re-enactments related to the city’s history in order to create a more hands-on experience. The reconstruction of part of the Nihonbashi bridge, as it was in its original 1603 form, is one of the museum’s main attractions and each year, thousands of people walk across it to travel back through time. One of the venue’s most unique characteristics is the importance that is given to these reconstructions, whether life-sized or in miniature. They allow visitors to lose themselves in the past. “People like Nihonbashi a lot, as well as Nakamura-za,” explains Iizuka, pointing out the building situated below the famous bridge. Nakamura-za is a theatre that was built in 1628 in Kyobashi, where the first performances of Kabuki were given in Edo. It moved several times before burning down in January 1893.This theatre represents the vibrant history of entertainment in the capital and is a great draw for the museum, as it is used to give many performances, especially of rakugo (a comedy spectacle that also dates back to the beginning of the Edo period). “Visitors tend to enjoy visiting that part of the museum because there are very few buildings left from that prosperous period,” says the curator a little regretfully. This becomes obvious when walking down the aisles. People spend a lot of time looking at the models that bring to life the districts that were popular around the time when the shogun had succeeded in uniting the country and Edo had become its political centre, replacing the ancient imperial city of Kyoto, which had become mired in formal tradition and lacked the same vital energy.

Visitors are fascinated with the model of Ryogoku and its famous bridge from which fireworks were let off over the Sumida. They discover a place where the population came to have fun and relax and also enjoy the reconstruction of the area in which the original Mitsui shop was founded in 1683. The detailing of the models, the attitude and the gestures of the miniature characters are the subject of many conversations among visitors. Children enjoy finding out how their counterparts used to play in the past and the adults learn about how day-to-day business was carried out. They can even practise carrying a palanquin (covered litter). One of the museum’s greatest strengths is the variety and imagination of all the different experiences on offer. “We didn’t want to create a museum similar to all the others. We want people to become involved and have fun,” says Iizuka. This is confirmed by all the laughter coming from those taking turns carrying the litter. The Edo period theme draws a huge number of Japanese visitors because the many films that have been set in that historical era make it immediately recognizable and relatable However, the museum is not limited to the 18th century.

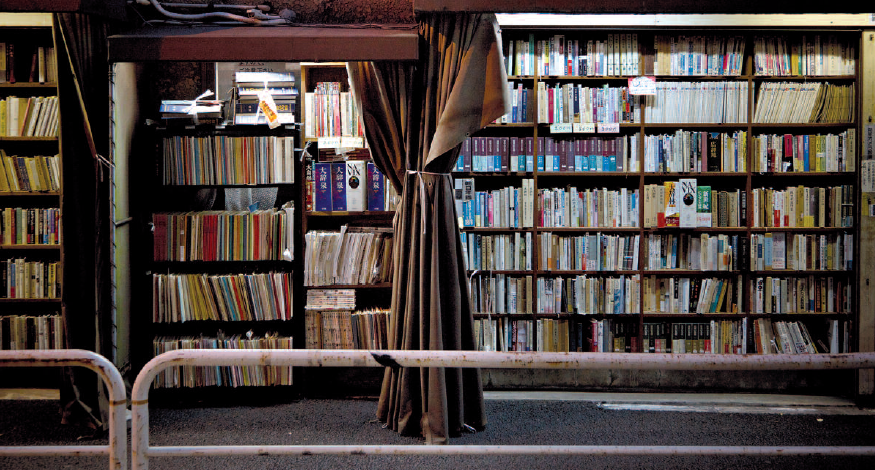

Different periods are on show in the less prominent parts and the founders of the museum have strived display everyday life throughout the whole of Tokyo’s colourful history, so you can also see the interiors of apartments from periods closer to the current era. The curator admits that visitors usually spend less time in the part devoted to modern Tokyo and it is undeniable that these exhibits do not evoke the same magic as those dedicated to the edo period. The 1923 earthquake is depicted, as well as the bombing during the Second World War and the first years of reconstruction with the increase in black market trading in Shinjuku. This part of the museum is still just as interesting as the rest, so the managers are thinking of renovating it in order to attract more people. Another one of the Edo-Tokyo Museum’s strengths is its ability to organize temporary exhibitions several times a year, related to various themes.

This allows them to highlight a particular historical era, to celebrate a personality, or to exhibit various objects that cannot be put on regular display due to lack of space in the display cases. To celebrate the museum’s twentieth anniversary, a beautiful exhibition entitled “Meiji no kokoro” [The soul of the Meiji era], made up of objects, photos and writings belonging to American naturalist Edward Morse, has been organized in collaboration with the Peabody Esses Museum and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. A fine selection of period wood- block prints and engravings will take pride of place from the 2nd of January until the beginning of March and many foreign visitors are expected to be drawn by these works from the famous “Floating World” genre. It is worth taking your time looking around this museum as it is full of surprises. The many volunteer guides, mostly retired people who have a good knowledge of their city, will help you discover many more secrets about the capital and are a great bonus as, unfortunately, much of the foreign language information available (mostly in English) is quite limited. The museum management is aware of this shortcoming however and the choice of Tokyo to host the 2020 Olympic Games should encourage the Edo-Tokyo Museum to speed up its production of translated information and materials aimed at foreign tourists. In the meantime, don’t deprive yourself of such an enriching visit.

Odaira Namihei

Photo: A model representing Ryogoku district during the Edo era. This is where the Edo-Tokyo museum was built nearly four centuries later.

Edo Tokyo Hakubutsukan