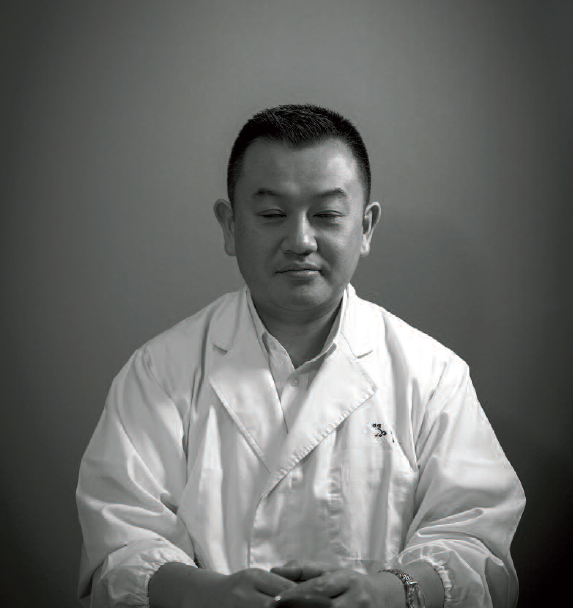

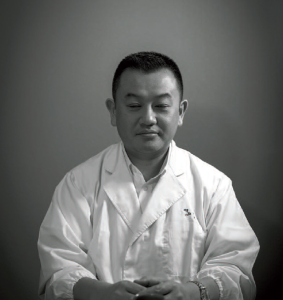

The owner of two Michelin starred restaurants in Tokyo is moving to Paris to introduce the best of his cuisine.

The owner of two Michelin starred restaurants in Tokyo is moving to Paris to introduce the best of his cuisine.

According to the respected Michelin guide, Tokyo rules the culinary world. Yet Okuda Toru manages to stand out with a whopping five stars under his belt. Not content with owning three-starred Kojyu and two-starred Ginza Okuda, the 44-year-old chef has recently gone international by opening a new restaurant in Paris.

Why did you decide to open a restaurant abroad?

Okuda Toru : For two reasons: First of all, washoku (Japanese cuisine) is getting more and more popular worldwide but it’s not easy to find really good Japanese food abroad. I’m not against foreign chefs, mind you. After all, there are many Japanese who make excellent French or Italian food. The problem is, a lot of dishes you find in Japanese restaurants abroad are below par. By opening my place in Paris I wanted to introduce people to authentic washoku made by expert Japanese staff in an authentic Japanese environment. The second reason is that although the world is experiencing a washoku boom, the culinary situation in Japan is far from good. For example, in the morning many people just have some bread and coffee and for dinner they can quickly fix some Chinese or Western dish at home. Japanese cooking is very labour intensive and takes time. It’s much easier to make a bowl of ramen or some pasta. Things have changed a lot. The new generations don’t learn traditional cooking from their mothers. They have been raised on a steady diet of convenience store snacks and fast food. Another problem – probably related to the previous one – is the shortage of chefs. Currently only about 10% of students attending cooking schools specialize in Japanese cuisine. Everybody wants to become a pastry chef or work in a French or Italian restaurant. Indeed, people who choose to learn Japanese cuisine have to face a rather bleak situation. Customers don’t want to spend more than 5,000 yen for a meal. In these conditions, it’s difficult to see a bright future for washoku.

Why did you choose Paris?

O. T. : Because it is the place the Japanese respect the most as far as culture and food are concerned. Exporting Japanese cuisine to Asia would be too easy because in many respects they are closer to Japan. As for New York, it wouldn’t have the same impact because the Americans are not famous for understanding fine food. But Paris is different; it’s the ultimate challenge. One more reason for choosing Paris was that cutting-edge French cuisine has recently been influenced by kaiseki (traditional Japanese cuisine) both in food seasoning and presentation. So I think the French are ready to experience authentic kaiseki – something that until now you could only get in Japan.

What is the biggest problem you have had in bringing your cuisine abroad?

O. T. : Finding good ingredients is a real headache. You can pretty much eat excellent French, Italian or Chinese food everywhere, but you can’t really make good washoku outside Japan, and the reason is because it is exceedingly difficult to obtain the right ingredients. Kaiseki cuisine in particular values subtle natural flavours over heavy seasoning. That’s why ingredients must always be fresh, local and seasonal. Yet in France there are strict rules regarding food imports. Luckily, now there are ingredients you can easily get in Europe, like soy sauce and miso (bean paste). We have also been able to find certain Japanese vegetables in France, thanks to Nantes-based farmer Olivier Durand, and the beef comes from famous Parisian butcher Hugo Desnoyer. The real problem is seafood, especially in a country like France whose cuisine values meat over fish.

Here your only options are sole and lobster. How do you plan to solve these problems in Paris?

O.T. :Next year I’m going to open a fish shop in Paris so I will be able to prepare fish the Japanese way. In France they just catch the fish and put it in freezers, but in Japan we use traditional ikejime techniques which involve keeping the fish alive in a tank so we can kill it immediately before cooking; or we drain blood from a live fish in order to keep it fresh. More than once I’ve eaten at a French restaurant and thought how much better the fish would have tasted if treated the ikejime way.

Do you think that your innovations are going to change the way food and eating are regarded?

O. T. : That’s my hope. Once people see how good our fish tastes they will realize they don’t need to add butter or other condiments. And once Paris changes, the rest of France will follow, then the whole of Europe and America. It will be a revolution. But first I need our government to negotiate some changes in the trade treaties between Japan and France and lift the bans on exporting food to that country. If I can find a way to open a gap in the system, I believe we can gradually change it for the better. Now it’s the time to take kaiseki out of Ginza and Gion and into the wider world of international cuisine, and I would like to help bring about this revolution.

Interview by G.S.

Photo: Irwin Wong