We investigated how the relationship the Japanese have with ekiben has changed over the last few decades.

We investigated how the relationship the Japanese have with ekiben has changed over the last few decades.

For many people in Japan, ekiben conjure up bucolic images of local trains slowly following the contours of the island or climbing steep mountains. This romantic side of travelling has not been tainted by the advent of the futuristic Shinkansen, but the economic reality that many ekiben makers have to face nowadays is certainly harsher than in the 1960s or ‘70s. Ekiben’s popularity peaked in the mid-50s, about ten years before the Shinkansen began operating, and since then sales have gradually gone down for a number of reasons. For one thing, the Bullet Train has greatly shortened travel time, thus allowing people precious little time to savour their lunchboxes. Also, some people prefer to buy cheaper food, as ekiben are relatively expensive. Then one has to consider the competition from other forms of transport as more and more people now opt to travel by car, long-distance bus or plane. As a result, the overall number of ekiben producers has dwindled.

However, one of the major reasons for the decline can be found in the rail transport business itself: the JR group that controls a good part of intercity rail services constantly favours its subsidiary ekiben producer companies while expanding its network of outlets in every corner of the rail network, thus causing more and more local companies to go out of business. Even so, ekiben remain very popular among travel fans, train otaku and foodies. Even now, about 3,000 different varieties are produced around Japan. According to ekiben wrapper collector Uesugi Tsuyoshi it is true that travellers buy fewer than before but on the other hand there are now more and more people who buy them at special fairs held inside department stores. “The thing is,” Uesugi says, “many middle-aged people and baby boomers feel a lot of nostalgia for both their home towns and the ‘good old times’ and ekiben are part of this attitude towards the past. So in a sense the link between travelling and ekiben has become weaker and these lunchboxes have become a sort of soul food which fuels people’s sense of nostalgia”. Travel journalist and food analyst Kobayashi Shinobu confirms Uesugi’s viewpoint. “The role of ekiben has changed,” she says. “They used to be a necessity for travellers, but now they seem to have become more akin to a special souvenir of a particular locality”. Kobayashi, a so-called “ekiben critic” has eaten her way through 5,000 ekiben while travelling the length and breadth of the country for the past 20 years. She sees the future of ekiben as a new class of gourmet food. “Many ekiben are made with 10 or more ingredients and prepared and seasoned in so many different ways. Recently you also see more and more “exotic” ekiben, like the “Koshu Wine Lunch” that is filled with foods that go well with wine, including diced steak or Spanish omelette, and it even comes with a small plastic wine glass,” she says. Among the more traditional offerings, ekiben from Tohoku seem to be particularly popular. Ekibenya Matsuri, arguably the biggest outlet in the country offering 170 varieties and selling around 10,000 boxes each day (with peaks of almost 20,000), since its opening last August inside Tokyo Station has periodically published a top ten list of best-selling ekiben.

Among them, specialities from the northeastern region, which was badly hit by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, always figure prominently, with Gyuniku Domannaka from Yonezawa (Yamagata Prefecture) in the lead. According to Uesugi, Tohoku’s popularity is partly due to the fact that people want to cheer themselves up and help the region’s recovery. “The disaster has badly affected the business, not only in Tohoku,” he says. “In Nagano prefecture, for example, a popular maker that had been founded in 1903 was forced to close down when people went into mourning and stopped buying ekiben”. However, Uesugi believes that Tohoku ekiben are so popular because people just simply like the food. “In Tohoku there are many kinds of beef (Yonezawa, Maezawa, etc.) and Sendai is famous for its beef tongue. Take, for example, the best-selling “Gyuniku Domannaka”. It’s an ekiben that uses local rice topped with domesticallyproduced Yonezawa beef cooked in the style of sukiyaki, a dish of thinly sliced beef flavoured with sugar, soy sauce and sake. It is so popular that it is sold not only at Yonezawa Station, but also on the Yamagata Shinkansen Line as well as at such major stations as Tokyo, Ueno and Omiya”. As mentioned above, ekiben fairs play a central role in the retail business, especially in department stores nationwide. The first was held in Tokyo in 1966 during the New Year holiday. There were around 200 kinds for sale and in the end 400,000 boxes were sold in just a couple of weeks, generating around 600 million yen in sales. Since then winter – and January in particular – has become the premier season for such events, each year attracting 20%–30% more visitors than usual. To give an example, last year the annual fair in Keio Department Store in Tokyo’s Shinjuku Station sold 283,726 ekiben of 160 kinds in 13 days. The most popular was “Ikameshi” (squid stuffed with sticky rice) from Hokkaido prefecture, an area famous for its seafood, of which 56,102 were sold during the fair. At 470 yen, it is much cheaper than the average ekiben and its popularity shows how local gourmets want to try the best food the country can offer, even in these times of austerity.

Gianni Simone

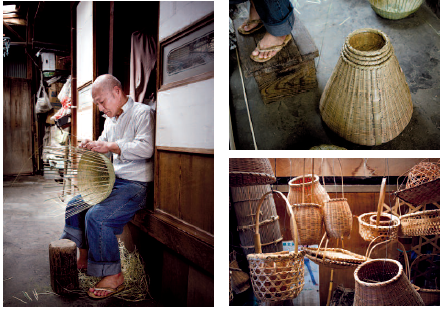

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat