As you move away from the louder streets in the neighbourhood, you may have a few surprising encounters.

As you move away from the louder streets in the neighbourhood, you may have a few surprising encounters.

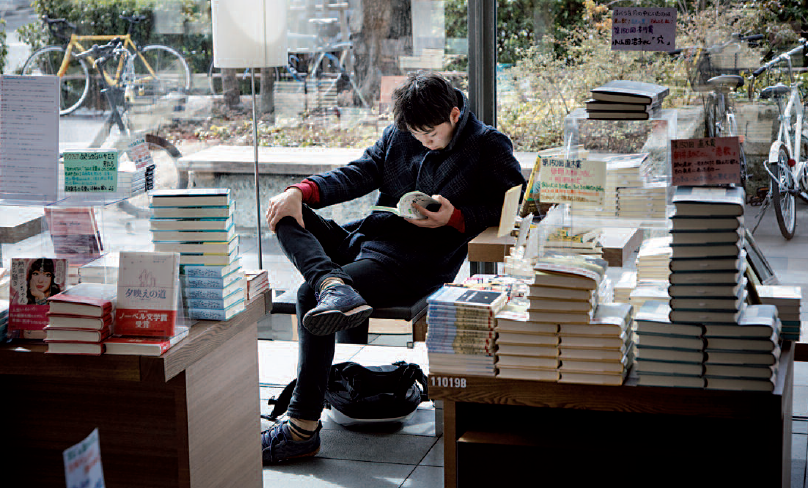

Around the back of the trendiest streets in Harajuku, there is a tiny neighbourhood that has preserved all of its mystery. Dotted with wholesalers and cafes frequented by elegantly dressed locals, Jingu-mae 2-chome Street becomes more and more interesting the further you go down it. The street itself actually branches into two roads, which lead to the remains of the Olympic complex. Walking on the left you will pass by one of the local shrines and on the right the Blood of Poets bar and the haunted Sendagaya tunnel. At the junction between the two stands the the Bonobo bar, marked out by the sign from an old liquor store, which used to be owned by a Taiwanese man, hanging in pride of place, exactly where it has done for the past 50 years. A bar, a club, a noodle bar and a tapas bar, the Bonobo is all of these things as well as a communal meeting place for music-lovers and a hotspot for crazy, talented artists.

Around 5 pm, Jingu-mae Street lights up as offices close for the day. Ug (Uji) Ueno arrives in his famous “sanctuary-car”, bedecked in leaves and branches, and parks in the middle of the street outside the Bonobo without anyone batting an eyelid. An old woman waves hello to Ueno-san from her grocery shop and then takes a picture with her phone. Nobody ever gets used to Ug’s car, it always provokes amazement, fear or laughter with a 3 metre high and 5 metre long pile of branches sits on the roof like a nest. “It helps to advertise my current hanaike exhibition!” he says. Based on ikebana, hanaike is floral art that can measure up to the enormous scale of this artists’ work. “I discovered ikebana when I was 19 and I would imagine people in kimonos, on a mat, contemplating. But in reality this art is much more aggressive and bold”. The Bonobo’s ground floor is the perfect illustration of Ug’s wild ikebana. It hangs down from the ceiling, with branches of all shapes and sizes that knot and swirl around each other above the DJ’s booth, and according to the season, it can include branches from cherry trees or hydrangeas. Ueno met Sei Koichi, the Bonobo’s manager, four years ago. “At that time, the Bonobo had been half destroyed by a fire. Sei asked me to create a terrace and to decorate the bar. And I immediately thought of using bushes”. “This is Tora-san’s house.” says the owner. Sitting on a mat on the second floor of this strange house, named after a monkey and built like a cave, Sei remembers his friend who passed away 8 years ago. “Tora-san was an old alcoholic. He also created the country’s best audio system in order to listen to Miles Davis properly. He lived on the second floor of this house that was used as a rehersal studio”. This Korean, born in Yamagata prefecture in 1963 and brought up with the name Yoshimura Koichi, was the founder of the Bonobo and mad about music. He lived in New York were he played in experimental bands while working at NHK and brought back the spirit of the Loft and its mythical underground parties that inspired the Bonobo. He bought the house in 2005 after meeting Tora-san. “If I hadn’t bought it, there’d be a car park here instead. Tora-san was right to choose me. He couldn’t pay the rent and died 6 months later”. The Bonobo has been the subject of much harassment from estate agents. “I was offered 100 million yen for the site. I was crazy to refuse,” murmurs Sei. The fire happened after that, during the Obon holidays. “Everybody was off on holiday. The police said it was arson. So I took revenge by building a terrace and an outdoor bar!” The neighbourhood around Jungu-mae also boasts a cemetery, a Buddhist sanctuary and a haunted tunnel that runs alongside the old 1964 Olympic facilities. Sendagaya tunnel was built for the Olympic Games under a cemetery, despite warnings to the contrary. It has since been classified as a “hotspot” for ghostly apparitions, as well as suicides. At the Senjuin traffic lights (the hermitage) outside the Victors building, is a very conspicuous house completely covered in leaves. A Japanese meddler tree spreads its branches over the entrance. Nothing would lead you to believe that it is inhabited: the windows are closed and obscured by ivy, but then the light comes on, and all you can think of is running away. A little further down the road is a black building that contains the Blood of Poets bar with a replica of the Mona Lisa as its sign. In an ambiance halfway between new wave and Cocteau, a Japanese Rastafarian drinks pastis at the counter. As a beat generation photographer and a great poetry enthusiast, the owner of the place, Fujimoto, opened yet another bar on the ground floor call Howl. However, the most mysterious and alluring bar in these parts has to be Sakura-san. Hidden at the bottom of a street, it is a refuge for the neighbourhood’s workers, although it has room for 10 customers at most.

The proprietor, Sakura-san himself, a tanned fifty-something, used to be an architect like his father and son. “I left the family business because I hated the accounting.” he says. He rebuilt this bar that used to be a warehouse, but kept the wooden structure and the outside entrance. It isn’t surprising that there’s neither a door nor a sign for this surf lover’s establishment. While the bar’s regulars come and go, Sakurasan remembers his first bar. “It was the Kilala bar, further up towards Harajuku. I don’t go there anymore, it’s haunted!”. The conversation suddenly takes off. Several customers remember the bar. “It wasn’t just Sakura-san. Everybody could see the ghost!” says Miyoshi, an engineer. “One night, quite late, we were 4 or 5 mates hanging out, and it was humid and warm. The ghost entered through the window like a draught. It just stayed there, standing. It was a man, a poltergeist,” says Sakura-san, as Ai-san shrieks that she would have loved to have seen him as well. “When you came it was too dry, that’s why you didn’t see him. Japanese ghosts like humidity”. It’s past 7 pm, the Bonobo’s outside bar lights up and a table is put outside on the pavement. The Chie bar, named after its manager, is opening up. “It’s not really legal to set up outside, but when the police turn up, all they find is a bunch of locals sitting around,” says Seisan with a smile. When it closes early in the morning, the bar turns into Usagi Udon, a noodle bar open every day for lunch. The Bonobo’s dance floor turns into a little canteen where the neighbourhood’s office workers come to eat. It’s great fun to see these well dressed men loudly slurping their soup to the rhythm of Ska music amid Ug’s bushy decor. Besides its delicious udon, Usagi is noteworthy for changing its manager every two years. “It’s to avoid boredom,” says Kisshin, the chef. Tokyo is a capital that continually changes and is known for destroying and reconstructing according to the latest trends, but in this small part of Harajuku there remains a bunch of hardliners that prefers to hold on to the existing framework and heart of the area.

Alissa Descotes-Toyosaki

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat