In a remarkable movie, Sono Sion illustrates the absurdity of the system’s response after a disaster in a magnificently poetic way.

In a remarkable movie, Sono Sion illustrates the absurdity of the system’s response after a disaster in a magnificently poetic way.

Sono Sion is one of the most interesting film directors to emerge from Japanese cinema in the past few years. He has built a solid reputation in his country and abroad with his powerful and sometimes disturbing films. A frequent presence at festivals, in film after film, he has proved his talent as someone who refuses to conform to a particular discipline or code of conduct. Like Tomita Katsuya, the director of Saudade (2012), who was doubtless inspired by him, Sono defends his freedom to choose what to create. For him, a film is a way of making things change, of encouraging the viewer to question the world around them. Deeply moved by the tragic events of the 11th of March 2011, Sono Sion wanted to express in his own words how shocked his country was by the earthquake and the tsunami. In Himizu, released in 2011 and presented at the Venice Festival that same year, he tells the story of two young teenagers caught in a natural disaster and facing the expectations of a society that everyone should unite to overcome it. However, these two characters are unsuccessful in becoming part of that impulse. They feel cut off from the rest of the world and express their anger in a magnificent whirlwind directed with gusto by a director who demonstrates a great deal more sensitivity than his work would at first suggest.

Sono Sion is a poet of deep sensibility, as was the late and greatly missed Wakamatsu Koji. His interest in the events of March 2011 could not be limited to just one film. “The first film laid the foundations for a second one,” he said when The Land of Hope (Kibo no kuni) was released last October in Tokyo. Yet it might never have seen daylight, as he initially failed to find the money to produce the film. The topic, human loss after a nuclear accident such as Fukushima, did not enthuse producers in a country in which “nuclear energy is still a taboo subject”. Thanks in part to money that came from Great Britain, Sono Sion was able to direct this work, intended as a manifesto, in which he once again expresses his deep anger. He wanted to demonstrate through fiction what people, victims of the disaster, felt deep down, people who in reality had no means of expressing themselves openly in the media. This story of two families living next door to each other, separated by a fence marking the creation of an exclusion zone, is inspired by true events. “A Kafkaesque reality,” says the director. This is the reality that the director vehemently denounces and, without imposing his version of the truth, he succeeds in encouraging the viewer to undertake some self-examination. A great achievement!

Odaira Namihei

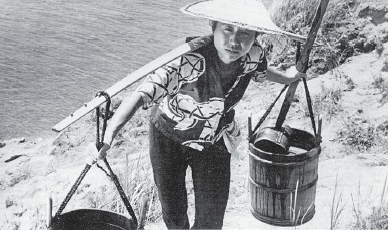

Photo: Third Windows Films