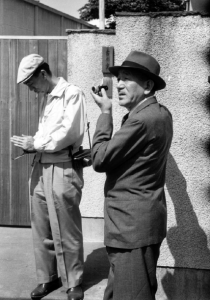

In several of his movies, Ozu Yasujiro placed his camera in Shitamachi’s popular quarters, in Tokyo.

In several of his movies, Ozu Yasujiro placed his camera in Shitamachi’s popular quarters, in Tokyo.

Ozu Yasujiro’s films tend to impress a distinctive mood on the viewer. Rather than a particular place (e.g. Nouvelle Vague’s Paris or John Ford’s Monument Valley), we remember the quintessential Japanese-style rooms where his quiet family dramas slowly unfold. Yet Ozu’s film locations changed through the years according to where he lived and the kind of stories he wanted to tell. Many of his better known films, which focus on middle-class families, were made in the 1940s and ‘50s after he moved with his mother and brother to Takanawa, an up-market area in western Tokyo, and some of his later works take place in Kamakura, a small town south of Tokyo where he moved in 1952. However, for many years he lived in Fukagawa – a working-class district in east Tokyo where he was born in 1903 and spent most of his youth – and some of his best early movies reflect those surroundings. Most people know Tokyo through its more glamorous and eye-catching spots like Shibuya, Ginza and Akihabara. In comparison, the eastern districts across the Sumida River look and feel like a different world. Even for many Tokyoites, Koto ward, where Fukagawa is situated, represents a place that in many respects has disappeared – the old city with its humble traditions and unrefined appetites. If you want to have a taste of Ozu’s Fukagawa you can start with a couple of his best silent films. “Dekigokoro” (Passing Fancy, 1933) and “Tokyo no yado” (An Inn in Tokyo, 1935) are part of the so-called “Kihachi trilogy” that chronicles the misadventures of Kihachi, a typical Edokko (true Tokyoite) as he tries to make ends meet. While Ozu’s earlier films were Hollywood-inspired light comedies about youth and college, Dekigokoro shows a new interest in the grittier side of life, probably because Ozu’s financial situation, like that of his penniless protagonist, was not very good at that time. The Tokyo we see in this story is a typical shitamachi (working-class district). Since the 17th century, rice, oil, sake and salt merchants had begun to build their warehouses in the eastern part of the city where they had easy access to the sea. The most precious product of all though, was wood and all the timber merchants had their wharves and warehouses in an area called Kiba (literally meaning “The timber area”).

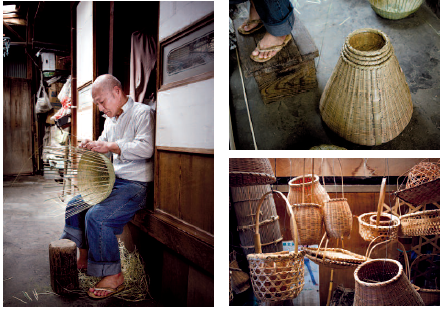

Today Kiba has lost its working-class atmosphere and has become a big residential area, the only apparent remnant of the old times being Tsuru-no-hashi, a wooden bridge built in the traditional style. Yet even now a stroll through Fukagawa reveals a few small workshops with their backyards full of long wooden planks. As for the timber-related businesses, they have moved further south to Shin Kiba (New new timber area) – a district that in Ozu’s time literally didn’t even exist. Until several years ago, modern day Tokyo’s southeastern districts that face out onto the sea were nothing more than a collection of scattered islets. It is not an exaggeration to say that most of Fukagawa’s foundations are made of rubbish – the preferred material used by the local government to reclaim the many swamps and tidal flats in the area as well as to build the artificial islands in Tokyo Bay. Fukagawa was chosen as one of Tokyo’s first industrial zones. The country’s first Western shipyard, cement works, sugar refineries and chemical fertilizer plants were opened here (Ozu himself was the son of a fertilizer wholesaler). Both in Dekigokoro and Tokyo no yado, as well as in the post-war film “Kaze no naka no mendori” (A Hen in the Wind, 1948), gas tanks and chimneys feature prominently in the suburban landscape. For many years all this activity was a blessing but it ultimately led to Fukagawa’s greatest tragedy. During the night of the 9th of March 1945, over 300 American B-29s dropped 700,000 bombs on Tokyo’s heavily populated shitamachi where most of the factories were concentrated. The air raid obliterated 40% of Tokyo and killed 72,000 people. The morning after, the whole of Koto ward had turned into a flat wasteland. Nothing was left of Fukagawa except for a few brick-built buildings. In Dekigokoro, the main character Kihachi works in a brewery – even though he spends most of the time idling around and running after young girls. In this and other films Ozu made in the early ’30s one can already see the utility poles that even today “adorn” most streets in Tokyo and other Japanese cities. Today Fukagawa’s streets are so quiet that if you go on an afternoon stroll you will see very few people outside, but in Dekigokoro and other movies of the same period life happens outdoors: Children play in the street and women chat with their neighbours while doing their chores, everybody squatting down in the typical Asian way. Dekigokoro’s generally light touch is replaced by a heavier mood in Tokyo no yado. This time Kihachi’s character is a widower with two small boys who desperately wanders from one factory to the next in search of a job. The bleak desert-like scenery through which father and children slowly walk offers a weird contrast between the factories, the lone dirt road and the grass growing all around them. The actual location is Minami Sunamachi, which is closer to Koto ward’s eastern border, and at the time felt more like countryside than a real suburban cityscape. Today, even this part of Tokyo has become a quiet residential neighborhood.

Fukagawa has recently opened a memorial centre to celebrate Ozu’s life and work. The place stands only a few metres away from Ozu Bridge – a nice coincidence even though the bridge’s name refers to a different Ozu family. For many reasons bridges and waterways are a very important feature of the area, as water has played a fundamental role in Fukagawa’s history, sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse. Canals were built for a number of purposes. One of them, the Onagi Canal, was built at the beginning of the 17th century and connected to Chiba prefecture in the east as well as to central Tokyo in order to provide the city with salt. Unfortunately, in addition to the usual problems (earthquakes and fires) that periodically destroyed a good part of the city, the districts east of the Sumida River also suffered periodical floods. Most were a mere nuisance but much more dangerous was the deadly combination of typhoons, earthquakes and tsunamis. The disaster that hit Fukagawa in 1854 killed over ten thousand people. Nowadays the banks of Fukagawa’s waterways have been reinforced and the chances of floods have been substantially reduced. A happier connection between Koto ward and water is its famous fish-based cuisine. The most popular dish was kabayaki (grilled eel) cooked, of course, in the Edo way, oily and salty, drenched in soy sauce. Another delicacy of the time was loach, a humble fish that today is only served in a couple of places in Tokyo, one of which – Iseki – is still located in Fukagawa. In Dekigokoro we see Kihachi discuss some matters of the heart with his friend while eating sushi. This dish became popular at the end of the 16th century and one of Tokyo’s (then called Edo) best sushi restaurants was located in Fukagawa. It was called Kashiwaya and served mazezushi (mixed sushi) and hayazuke, sushi that is prepared one day before being served – something that today’s gourmets would consider sacrilege. Some of the eateries and teahouses in the area were places where, according to the 1818 Illustrated Gazetteer of Famous Places in Edo, “the sound of singing to the accompaniment of the samisen never ceases”. Even more than for the food, these places were popular for the charm and musical skill of their girls. The higher ranked ones called themselves geisha but were in fact prostitutes. Even Kihachi can be seen drowning his sorrows in drink while a young woman with a samisen keeps him company. Fukagawa was in fact one of the most popular districts where men could seek the pleasures of the flesh in one of its seven unlicensed quarters. Now even these places are only a past memory, but we can still savour some of the old atmosphere. We only need to step beyond Eitai Road’s incessant traffic and explore its many backstreets to find the same tiny shops selling senbei (rice crackers), manju (bean-filled buns) and tsukudani (little fish marinated in soy sauce).

Gianni Simone

Photo: Shochiku Co., Ltd.