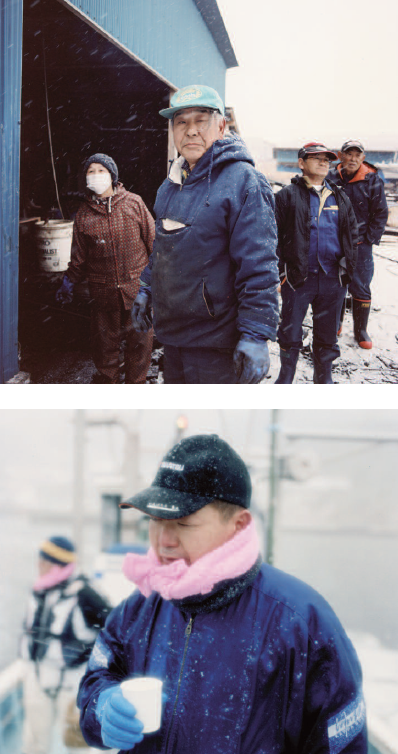

The tragic events of the 11th of March 2011 affected this couple’s dream of having many children.

The tragic events of the 11th of March 2011 affected this couple’s dream of having many children.

Saitama is a suburb in the northeast of Tokyo. We’re in a trendy two-room flat in which Ida Andre and his wife Tomoko live. Lukas, their son, is cuddled up in his mother’s arms. With his tousled hair and his mischievous pout, he stares at the people around him with curiosity, before burying his face with a smile in his mother’s shoulder. Lukas was born in December 2011. He has little chubby cheeks and legs. A shy, smiling boy: he makes sure his mother is never far away. And when his parents have their backs turned, he enjoys typing on his father’s computer, although he isn’t allowed to. His parents watch him, delighted. Andre and Tomoko, 33 and 35 years old respectively, started thinking seriously about having a child three years ago. They’ve known each other since Fukuoka University in Kyushu, where they studied together. “My family is Japanese, but they live in Brazil, and I was born in São Paulo,” Andre explains. I came to Japan to study in 2005, and I stayed”. Tomoko is from Mie, the prefecture south of Kansai. “For a long time, we thought of having three children,” says Andre. “But what with the difficulties we had trying to have Lukas, we thought of giving up on having a big family,” he says gloomily. Tomoko’s pregnancy was a morally testing time, March 2011. Tomoko learned of her pregnancy four days before the Earthquake took place. She had been carrying her child for 6 weeks. “I was so happy to be pregnant. But then everything went dark. All I wanted was to protect my baby. I felt confused”. After the earthquake and then the Fukushima Dai-ichi power plant accident, the young mother’s worries intensified. “I didn’t dare drink tap water anymore. Nor go shopping. Which vegetables could I risk buying? I had no idea. So I started buying bottled water in shops and ordering food over the internet to ensure precise traceability”. Tomoko is outraged when she remembers this worrying time in her life. “We suffered from lack of information from the government. It’s true. We were told that food with under 10% microsieverts of radiation was edible and not dangerous for human beings – but what about my baby? I was uncertain”. It was out of the question for Tomoko’s baby to become a guinea pig. For the six months after the earthquake, Tomoko and Andre washed their vegetables with mineral water. “The cost of bottled water rose at that time,” says Andre. There were regular medical appointments though no more or less than for a regular pregnancy, although the stress was more intense. “We thought of leaving for Brazil, to meet up with my husband’s family,” Tomoko admits. “We didn’t feel it was safe to bring up our child here. I even thought the worst: I thought of aborting”. Now, Lukas is here. “When I look at him, I am glad I endured all the fear, and that he is here and in good health,” Tomoko smiles. Step by step, she started using tap water again, because “I can now check the quality of the city’s water on the internet”. Life goes on. Lukas will soon be a year and a half and Tomoko and Andre are starting to think about having a large family again. Last October, Tomoko’s maternity leave came to an end and she went back to work. The nursery school won’t admit Lukas until April so, “my mother came from Brazil to take care of Lukas for the time being, until everything is in order,” Andre explains. As for Tomoko, she has negotiated to be allowed to leave work when the nursery closes. “I’m lucky. This kind of arrangement is rare for full-time positions: my bosses are very understanding”.

J. F.

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat