Japan’s former cultural and intellectual centre, in the north east of the country, makes a beautiful stop off the beaten track.

Japan’s former cultural and intellectual centre, in the north east of the country, makes a beautiful stop off the beaten track.

Iwate’s main city was hit by last year’s earthquake and tsunami. The effects of the disaster are still very obvious along the Pacific coast, but many inland areas were spared from nature’s rage. A case in point is Hiraizumi, which was recently registered as a World Heritage Site by Unesco. This news was greeted by a wave of enthusiasm at a time when the local population needed a morale boost. Hiraizumi had suffered indirectly from the disaster because many tourists decided to avoid that part of the country due to the aftershock and the situation at Fukushima’s nuclear power station, although both occurred far away. So people in Hiraizumi warmly welcomed Unesco’s recognition of their city, which was originally created to represent ‘heaven on earth’ and is entirely dedicated to Buddhist principles. Brought into being by the Fujiwara clan after leaving Kyoto, principally by Kiyohira who had made a fortune from gold, the city increased in importance during the 12th century when many temples and gardens were built. Most of these were destroyed in attacks by Shogun Yoritomo’s army. But the monuments that are still standing easily allow you to imagine how wealthy the city used to be, and they are well worth a visit.

Hiraizumi is easily accessible with ease by train, and requires a stay of at least a day, if not two, in order to discover all its secrets and charms. The Fujiwara clan made strenuous efforts to succeed in building an intellectual and cultural centre as prestigious as Kyoto. The most significant vestiges of this past splendour are located in the north and the south of the city. It is recommended that a traveller with little time go to Chusonji, which is accessible by RunRun bus (4 minutes) or on foot (20 minutes). The walk is very attractive, especially in spring or autumn, when nature displays its beautiful colours. Chuson-ji includes a park full of temples and is located in the forest. You enter it via Tsukimizaka, a path bordered with Japanese cypresses that were planted over 400 years ago. Depending on the season, many Japanese take the time to admire the beauty of these trees, their leaves changing to wonderful colours in October and November, or covered in white under layers of snow in winter. The walk is very pleasant, and is a reminder of the important role nature plays in Japanese culture.

In Chuson-ji it is even more obvious that its builders set out to create a represention of heaven on earth. In 850, Ennon, a monk, started building temples in Chuson-ji, but it was only under the influence of Fujiwara Kiyohira that the park became an important religious centre with the construction of over 40 temples. Only the beautiful Konjiki-do (Gold Hall) remains. Completed in 1124, it is covered with gold leaf and mother-of-pearl from Okinawa. There are 33 statues inside the sanctuary, of which the principal and most important represents Amida Nyorai Buddha. Four members of the Fujiwara clan lie under it. This amazing building, registered by the authorities as a national treasure, inspired Basho the poet, father of haiku, who visited Chuson-ji during his Northern trek in 1689. In his travel journal Oku No Hosomichi (Back Roads to Far Towns), he described the amazement he felt when he saw the Konjiki-do or Hikari-do (Light Hall) :

Samidare no

Furi nokoshite ya

Hikari-do

The May rains

Falling, seem to spare

The Light Hall

A statue of the poet has been placed nearby, as a reminder of his travels in the area. The Gold Hall and its amazing Amida Nyorai Buddha benefit from being under the secure gaze of one of Japan’s most famous writers. Lovers of Haiku often stop at Basho’s statue to pay tribute to him before continuing to walk along the site’s many paths. They then meet up at the Kyuoi-do, the ancient wooden building that protected the Konjiki-do from wind and snow. However lacking in ostentation this fourteenth -century building may look, it is worth seeing if only for the ingenuity of its architecture, or to experience walking in the footsteps of the great poet who was here three centuries ago. Approximately 100 metres away is a noh theatre stage which was rebuilt in 1853. It is the only one of its kind in the north east of the archipelago. Plays are performed here from time to time, but the stage is mainly used during the Fujiwara Festival (Fujiwara Matsuri) that takes place every year in May and November. The May celebration in 2011 was cancelled as a consequence of the earthquake. It is one of Hiraizumi’s great attractions as it takes place in May, during ‘golden week’ when most Japanese take a few days off from work. You can end your stay in Chuson-ji by visiting Hondo, the main building at the centre of the park. It was rebuilt in 1909 and is the largest construction on the site. However, you may prefer to go to the Shohuan teahouse to taste delicious green tea and Japanese pastries while contemplating the gardens.

When the time comes to leave, other discoveries await if you are not in a hurry to get back on the train. The bus runs by the station, but it can also take you to Motsu-ji, south of the city. Built in 850 by Jika Kidaishi, and with thanks to investments from the Fujiwaras’, this monastery was long considered to be one of the most beautiful in the archipelago before a fire destroyed it in 1226. Its huge garden, which represents the heaven on earth of the Pure Land Buddha, is magnificent. It surrounds the Great Spring Pond (Oizumigaike), the only relic dating back to the Heian era and one of the rarest in the country. When walking through the garden you can see traces of where buildings previously stood, but above all you can enjoy nature once again. In June, when the flowers bloom, the Iris celebration (Ayame matsuri) should not be missed. Claude Monet, a lover of these flowers, would certainly have enjoyed painting this symphony in blue. It is a good place for meditation and poetry, and doubtless that is why a gigantic stone has been placed there on which a famous haiku by Matsuo Basho has been carved:

Natsukusa ya

Tsuwamono domo ga

Yume no ato

The summer grasses –

Of the brave soldiers’ dreams

The aftermath.

The poet walked up onto Takadachi hill, where Minamoto no Yoshitsune, one of Japan’s great heroes, met a tragic end. He fought as a warrior at the side of Minamoto no Yoritomo, a powerful lord who created the shogunate, but they soon became the worst of enemies. Despite the presence of his servant, Benkei, and unable to escape, he would still have ended up committing suicide. There is a memorial (Takadachi Gikei-do) to his name on the peak from where there is the most beautiful view of Hiraizumi and its surroundings. When Yoshitsune died, Yoritomo decided to raze Hiraizumi to the ground and destroy what the Fujiwaras had built. But for many, Yoshitsune did not die in Hiraizumi. They believe he fled to Mongolia with Benkei, where he changed his name to Gengis Khan, and misled his rival by leaving two lookalikes behind to die in their places. The locals carefully keep this legend alive, which also contributes to the charm of this town that is so proud of its past glory. Imagine going back in time. In this part of Japan where nature has been well preserved, it is easy to forget that we’re in the 21st century. On a foggy day, whether in Chuson-ji, Motsu-ji or Takadachi Gikei-do, if you close your eyes and concentrate, you might just hear the voices of warriors and Buddhist monks, or even of the poet Basho, rising up and thanking you for spending time in their company. The whole of the region, as well as Hiraizumi, needs tourists who are not afraid to take a step back in time, in order to return from their travels full of satisfaction and the secrets they have discovered.

Gabriel Bernard

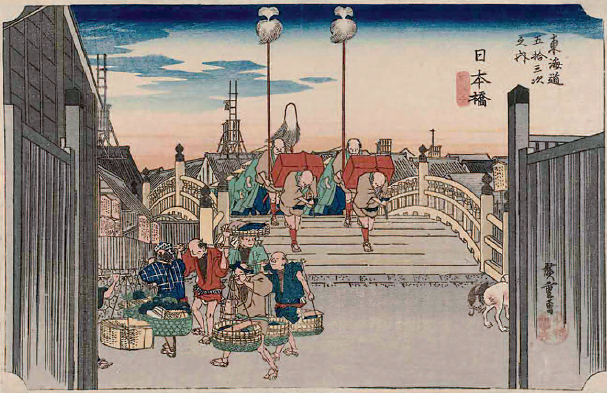

Photo: Gabriel Bernard