Amid the great loss of property and human life caused by the Great Kanto Earthquake, a particularly grisly and shameful detail that should not be forgotten is the fact that several thousand people – mainly Korean and Chinese immigrants but also local left-wing activists – were murdered after the disaster.

The massacre occurred over roughly five days. Therefore, when the Yamamoto Cabinet promulgated the order to maintain public order on 7 September most of the slaughter had already occurred. Eventually, the civil and political liberties of the citizens of the four affected prefectures of Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba were suspended until 15 November when martial law was finally lifted.

The exact number of victims is unknown because the Japanese authorities destroyed the evidence (including burning the corpses of the victims) and resorted to other means to obstruct investigations. However, while estimates vary widely, most historians now agree that some 6,000 people were killed during the first few days following the disaster. The Korean Disaster Relief Team organized by Korean students and church leaders in Japan conducted an investigation about one month after the earthquake. They counted 1,781 dead in Tokyo (roughly 20% of the city’s Korean population) and 3,999 in Yokohama. Historian Kajimura Hideki later questioned the latter figure for possible double counting. Even so, the 2,000 victims he thought were closer to the truth represent 55% of the estimated Korean population of Yokohama at that time.

The officially accepted version of the slaughter is that the devastating effects of the earthquake threw public sentiment and social order into turmoil. In such extraordinary circumstances, civilians armed with bamboo spears, Japanese swords, and guns formed vigilante groups and attacked the two main ethnic minorities in Japan based on false rumours that they were causing riots, committing arson, poisoning wells and gang-raping women in Tokyo, Yokohama and other places in the Kanto region. However, documents and other sources of information that later came to light tell a very different truth: though some of those vigilante groups were created spontaneously in places that were affected by news reports, hearsay and rumours, others were organized under the initiative and guidance of the local police who were following government orders.

In fact, at that time, the Ministry of Home Affairs sent a message to police stations throughout the country, instructing them to “be careful, as Koreans are plotting violent crimes and riots, taking advantage of the chaos’’. This message was distributed to government agencies and newspapers, which in turn took care to spread the word among the population.

According to Hasegawa Kenji, a professor at the Yokohama National University and the author of “The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923” (Monumenta Nipponica, Volume 75, Number 1, 2020) the police had had begun to establish community vigilante groups in Kanagawa Prefecture roughly one year before the earthquake. “These groups conducted joint activities with the local police,” he says, “participating in arrests of suspected criminals, and they formed the organizational basis for the rapid proliferation of vigilante groups after the earthquake.”

Right-wing leader Uchida Ryohei later vehemently protested against police attempts to put all the blame for the killings on the vigilantes’ shoulders. He wrote that “the whole city witnessed police officers running around, shouting ‘when you see a Korean behaving violently, you may beat him to death on the spot’”. Also, as historians Kang Deok-sang and Keum Pyong-dong wrote in Koreans and the Great Kanto Earthquake, hundreds of armed soldiers were dispatched to Tokyo under the slogans “The enemy is in the imperial capital” and “The enemy means Koreans”.

While xenophobia and resistance against immigration certainly played a big part in the massacre, the widespread killing of Koreans is also seen as a way to punish Korea for the trouble caused a few years earlier. In particular, in 1919, thousands of people in Korea had called for independence and the end of forced assimilation into Japanese culture (Korea had been annexed to the Japanese Empire in 1910). What became known as the March 1st Movement eventually resulted in over 1,000 demonstrations in many cities, which were brutally suppressed by the Japanese military (according to Korean historian Park Eun-sik, about 7,500 people were killed, 16,000 were wounded and 46,000 were arrested).

Another Korean historian, Kang Deok Sang, highlighted the fact that some of the Japanese political leaders at the time of the 1923 earthquake and massacre (Home Minister Mizuno Rentaro, Tokyo Police Commissioner Akaike Atsushi and Tokyo Governor Usami Katsuo) were all in leadership positions in Korea at the time of the March 1st Movement, as vice governor, police commissioner, and home minister respectively.

Although the killing was in large part orchestrated by the authorities, it’s true that it not only spread like wildfire, but it quickly got out of hand. In their thirst for revenge, the mobs ended up lynching or injuring even Japanese citizens because they looked or sounded different. Throughout each city, individuals were stopped in the street and questioned about their origins. As many Koreans cannot be distinguished from the Japanese just by their appearance, one typical way to check their nationality was to order them to repeat certain phrases that Koreans found particularly hard to pronounce.

Among those who fell victim to this vocal examination were Japanese people who stuttered or had speach and hearing impairments and whose Japanese pronunciation was deemed suspect or unsatisfying. For the same reason, people who had moved to the Kanto region from rural areas and other prefectures were targeted because their speech patterns were different from the kind of Japanese spoken in Tokyo. In the so-called Kemigawa and Manuma Town incidents, for instance, the vigilantes murdered people from Okinawa, Akita and Mie prefectures including nine members of a family from Kagawa.

In Something Like an Autobiography, Kurosawa Akira recalled those days and a particular episode that directly involved his family. At the time, the future film director was in his second year of junior high school. After the earthquake, his father was mistaken for a Korean because he had a long beard, unusual among Japanese men. He was quickly surrounded by the mob and questioned about the graffiti he had apparently written on a well: according to the vigilantes, it was a sign that the Koreans would leave in places they had poisoned. Luckily, they eventually let Kurosawa’s father go.

On the other hand, it’s known that Akutagawa Ryunosuke, the author of two short stories that Kurosawa would turn into one of his masterpieces, Rashomon (1951), was active in one of the vigilante groups, but he probably did not take part in the massacres. Indeed, in October of the same year, he published an article in the Bungei Shunju magazine, “Words of a Vigilante”, in which he commented on the slaughter committed by such groups by stating that: “Nature looks coldly at our pain. We must pity those people who rejoice in such a situation – although it is easier to strangle an opponent than to win an argument.” Also, in the fifth instalment of “Notes on the Great Earthquake”, a series that appeared in Chuo Koron magazine in the same month, he criticized the murders and ridiculed the “good citizens” who had believed in false rumours about the Koreans.

Although the slaughter of Chinese immigrants was less thorough, it was equally brutal and indiscriminate and resulted in at least 600 dead. The epicentre of anti-Chinese activity was Oshima, in Minami Katsushika, one of the mostly working-class eastern suburbs of Tokyo. Even in this case, it was a fake news story that incited people to action. On 6 September, under the headline “People and Activists Commit Looting and Rape’’, the Shimotsuke Shimbun reported that a large number of Koreans and Chinese had entered empty houses and committed looting and rape at night supported by socialist troublemakers who hearing the cries of the victims “had sung revolutionary songs”.

It was only in the early 1970s that the first detailed Japanese studies of the Chinese massacre appear, authored by Matsuoka Bunpei and Ogawa Hiroshi respectively, who both used historical material from China. According to Ogawa, besides xenophobia and the usual labour disputes, the main reason for the massacre was the widespread resentment towards the Chinese rejection of the Twenty-One Demands (a list of secret demands issued by the Japanese government in 1915, which would have greatly extended Japanese control of China including giving Japan a decisive voice in finance, policing and government affairs) and the violent demonstrations which had followed restrictions on immigration of Chinese workers.

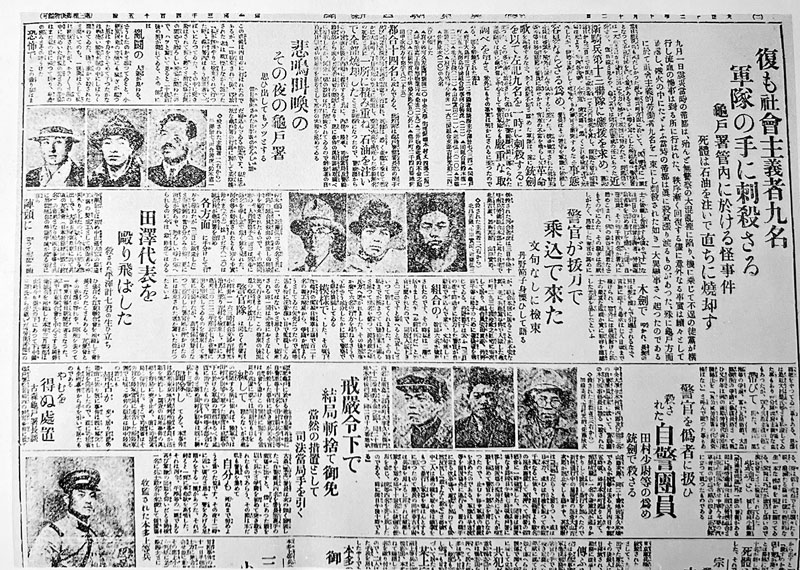

A third group that was targeted in the aftermath of the earthquake was left-wing activists and union leaders. Taisho Democracy – the liberal and democratic trend that characterized political life in Japan between the end of the Russo-Japanese War (1905) and the end of the Taisho era (1926) – had revitalized socialists’ resistance to the ruling powers, particularly the labour movement, the civil rights movement and the women’s movement. The army and police used the post-earthquake chaos as a unique opportunity to hunt down left-wingers throughout the Kanto region. The two most famous examples of this violent repression are the Kameido Incident, in which ten people were massacred by the army, and the Amakasu Incident, in which anarchists were killed by the military police.

In Kameido, a neighbourhood in east Tokyo, the local police began arresting known social activists on 3 September, suspecting that they would “spread disorder or foment revolution amid the confusion”. When the 13th Cavalry Regiment was called to the area on emergency duty, they murdered ten of them and disposed of their bodies, together with those of the Korean and Chinese massacre victims, along the banks of the Arakawa drainage canal. In the Amakasu Incident, which takes its name from Imperial Army officer Amakasu Masahiko, Osugi Sakae (an informal leader of the Japanese anarchist movement and the country’s first Esperanto teacher) and his wife, anarcha-feminist Ito Noe, were executed by a military police squad along with Osugi’s six-year-old nephew. Amakasu was sentenced to ten years in prison, but was pardoned three years later when Hirohito became Emperor of Japan.

Ironically enough, instead of plotting against the state, some of the socialists and Koreans had actually volunteered to help the victims of the earthquake. For instance, a large number of Korean labourers worked as longshoremen at the port of Yokohama. In March 1920, left-wing activist Yamaguchi Seiken established a union of day labourers in the city, and many Koreans joined the organization. An expert union organizer, Yamaguchi quickly formed an emergency food relief organization after the earthquake, and his men, including a group of Korean workers, began to feed local residents – a neighbourhood that was known to the police as a “socialist nest”. Yamaguchi was arrested and after being held in prison for several months, he was finally prosecuted for redistributing food and water from ruined houses to earthquake survivors without the permission of the homeowners. In July 1924, he was sentenced to two years in prison.

In the end, the violent repression of political dissent contributed to putting an end to the Taisho Democracy. As Joshua Hammer pointed out in “The Great Japan Earthquake of 1923” (Smithsonian magazine, May 2011), the Kanto earthquake “accelerated Japan’s drift toward militarism and war”.

Luckily, there were also cases where the targeted groups were helped. For example, the yakuza, who accepted Koreans among their membership, protected them from the lynch mobs. In another case, Okawa Tsunekichi, Chief of the Tsurumi Branch of the Kanagawa Police Station, is said to have protected hundreds of Koreans and Chinese from vigilantes, cracking down on rioters. In total, 745 Koreans (672 men and 73 women) were placed under protective custody in five facilities, and most were freed by the end of September, including 226 Koreans from Yokohama who were housed at the Army Artillery Arsenal in Yokosuka.

However, according to Hasegawa Kenji, the protective custody operations were not primarily about protecting Koreans but rather about safeguarding the state against them and other potential troublemakers. On 1 September, Crown Prince Hirohito and his entourage were supposed to travel through Yokohama to the resort town of Hakone, and the authorities devised several surveillance measures in order to ensure his safe passage to Hakone. Therefore, plans for such operations, including containing the Korean and socialist threat, were already partially in place on 1 September, the day of the earthquake.

The authorities banned any newspaper report on Korean killings until 21 October, and even when news of the slaughter slowly came to light in the press, the pursuit of those responsible for the massacres was not at the top of the authorities’ agenda, and most of the population had other things to worry about. The most important thing was maintaining public order and assisting disaster victims, and the military, government and police were praised for doing a good job, thus regaining the prestige they had lost in the previous 20 years.

On 5 September, in a secret memorandum entitled “Agreement Concerning the Korean Problem”, the authorities agreed “to create the impression (particularly overseas) that both Korean and Japanese ‘Reds’ had in fact encouraged acts of violence”. As a result, not only did they fail to pursue the real culprits for the killings but, on 21 October, when the ban on the press was finally lifted, the newspaper announced that the police were filing charges against 23 Korean suspects.

Japan’s reputation overseas was one of the issues that troubled the government the most. For example, when migrant workers from Wenzhou returned to China on 12 October, many injured people disembarked from the Yamashiro Maru, the ship on which they had travelled, and gave an account of the mass killings which had occurred in Oshima, causing uproar in the port. In China at the time, people were collecting and sending donations for the victims of the earthquake, but, understandably enough, public opinion changed dramatically after news of the slaughter became known.

To prevent such embarrassing news spreading abroad, the Tokyo police tasked a collaborationist group, the Soaikai, with arresting all the Koreans who were trying to leave the country and detaining them in camps in Honjo, a Tokyo neighbourhood. In the end, the those arrested came in handy when the Soaikai ordered 4,000 Koreans to undertake unpaid labour for over two months to clean up the city ruins.

Throughout human history, collective memory has tended to reflect master narratives of an event forged by leading social and political groups, and the Great Kanto Earthquake is no exception. All the official histories of the disaster that came out in the following years sought to shield the police and military from any blame, portraying them as heroic and selfless people who had tried in vain to extinguish violence and place Koreans under “protective custody” to shield them from the bloodthirsty mob.

While the official stance on those events has not changed, this year the Executive Committee for the 100-Year Memorial Meeting for Korean and Chinese Massacre Victims of the Great Kanto Earthquake, which consists of scholars, lawyers and journalists, has demanded that the government admit the role played by the authorities and provide compensation.

Unfortunately, xenophobia – especially directed toward the Korean and Chinese communities in Japan – and denialism have survived to this day. On 9 April 2000, for instance, then-Governor of Tokyo Ishihara Shintaro attended a Ground Self-Defence Force memorial ceremony. On that occasion, he famously stated that the military would be needed to suppress Sangokujin criminal activity in the event of a catastrophic disaster in Tokyo (Sangokujin is a derogatory term referring to immigrants from Korea and China).

Declarations such as Ishihara’s and those uttered by right-wing groups are still pretty common, helped by the fact that the Hate Speech Act, which was enacted by the National Diet in 2016, regulates but does not ban hate speech and sets no penalty for committing it. On the other hand, local governments such as Osaka and Kawasaki have established ordinances to prevent or ban hate speech.

Since 1974, every year on 1 September, a memorial ceremony for the Korean victims of the Great Kanto Earthquake has been held at Yokoamicho Park in Tokyo. Every year, successive governors of Tokyo have sent condolences. However, the current governor, Koike Yuriko, stopped sending condolences in 2017, a year after her inauguration. In its place, Koike sent a message in which she pointed out that “There are various interpretations of history”, and that anyway “There is no need for a separate letter of remembrance because we are mourning all the victims, including Koreans and Chinese’’. But the Tokyo Metropolitan Government went even further: on Memorial Day, it now allows a group of right-wing denialists to hold a gathering at a location nearby Yokoamicho Park, where they are free to shout anti-Korean slogans.

Maeda Akira, an Emeritus Professor at Tokyo Zokei University who specializes in human rights said: “In the past decade or so, there has been international debate about the denial, concealment and oblivion of historical facts. (…) Even in Japan, it would be better if open denial of serious human rights violations could be criminalized. In Japan, we have avoided responsibility through ambiguity. Not admitting the facts is the same as a second rape that hurts the victims again. Japan’s honourable position in the international community is undermined.”

Gianni Simone

To learn more on the subject, check out our other articles :

No. 133 [FOCUS] Great Kanto Earthquake

No.133 [TRAVEL] Waiting for the Big One

No.133 [INTERVIEW] Imaging disaster: Gennifer Weisenfeld

Follow us !